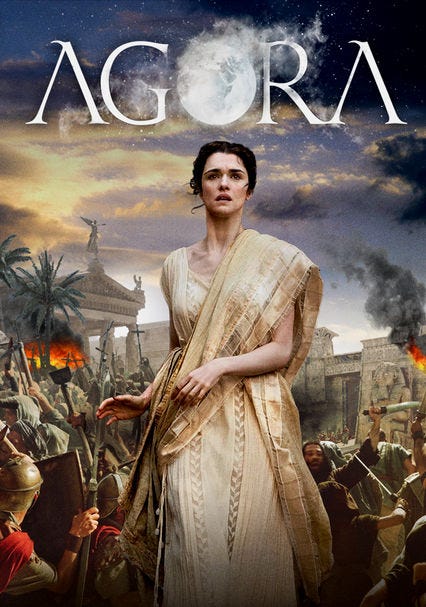

Historical Movie Review: Agora

(NOTE: I intended to write something for Good Friday, but this article was on the back burner, so I finished it up instead and originally posted it here. It’s an odd thing to talk about on this day, but history cannot be forgotten…)

I absolutely love history, and historical movies are a lot of fun. I normally prefer historical documentaries, as I like historical facts more than fiction, but I still have a soft spot for historical films. Sometimes fiction can be a lot of fun, and mainstream audiences (and myself) will sometimes find a person or time period that has slipped under their radar.

This was the case with the film Agora. I love the ancient world, and it’s a shame that good historical films very seldom take place in it. For most people, the Dark Ages of Europe are about as far back as they prefer to go, but I wish that more films of this sort came out.

The movie Agora is about the philosopher Hypatia of Alexandria, Egypt. Before I get into the film itself and how accurate it is, it’s important to set the stage somewhat and explain why Hypatia is such a popular character.

Who Was Hypatia of Alexandria

Hypatia was a philosopher and mathematician born sometime between 350–370 CE (AD). Her father was the mathematician Theon, who served as the last professor at the University of Alexandria. Despite women in this time period receiving little formal education, Theon tutored Hypatia in philosophy, math, and astronomy. We don’t know if Hypatia had any siblings or not, so perhaps the lack of sons could be a reason why Theon put so much effort into his daughter’s education.

Because of this, Hypatia grew up able to break through many barriers normally imposed upon women even of her class (her father’s school was extremely exclusive and prestigious, meant only for the most privileged of the day). We know absolutely nothing about her mother, however, and even the details of Hypatia’s life are a little sketchy, especially in comparison to what we know of her shocking death.

We know that she taught her Neoplatonist philosophy (as a side note, she taught Plotinus’ Neoplatonism, rejecting its more modern teachings by Iambluchus), math, astronomy, and also lectured on the writings of Aristotle and Plato, We don’t have any original works by her, but the popular thing of the day was to write a commentary on philosophy rather than develop it in your own way, and we do have bits of writing that we suspect was hers in this regard.

One of her contemporaries, the Christian historian Socrates of Constantinople, wrote this of her:

“There was a woman at Alexandria named Hypatia, daughter of the philosopher Theon, who made such attainments in literature and science, as to far surpass all philosophers of her own time. Having succeeded to the school of Plato and Plotinus, she explained the principles of philosophy to her auditors, many of whom came from a distance to receive her instructions. On account of the self-possession and ease of manner which she had acquired in consequence of the cultivation of her mind, she not infrequently appeared in public in the presence of the magistrates. Neither did she feel abashed in going to an assembly of men. For all men on account of her extraordinary dignity and virtue admired her the more.”

Other contemporaries have stated such things that she excelled her father at mathematics, was extraordinarily talented as an astronomer, was fair and beautiful, and was a lifelong virgin.

Setting the Stage: Alexandria, Egypt

Just given the name, you probably know that this city was founded by Alexander the Great, who insisted on founding an awful lot of Alexandrias in his attempt at world conquest. He drew up plans for the city himself before leaving his commander, Cleomenes, to actually build it.

The idea was for the city to be the seat of learning and wisdom, and the city points directly towards the mighty Athens. Indeed, Alexandria was considered only second to Athens when it came to learning and education in the ancient world. The city became home to the Great Library of Alexandria, which ultimately perished in a fire when Julius Caesar made a whoopsie while fighting a naval battle near its shores. I don’t think the world is finished mourning its loss yet, even if one could argue that the Internet has far surpassed the library’s potential.

Upon the city’s founding, scholars were so overzealous that travelers would be searched for books upon arrival. Any texts that were found were confiscated and brought to the library to be meticulously transcribed for anyone studying there. You may or may not have gotten your books back, and the time it takes to copy one is usually fairly long.

It was within those walls that many philosophers, mathematicians, and scientists (although science was usually lumped under the umbrella term “philosophy” back in the day) made incredible discoveries, including Heron of Alexandria, but that’s another article.

Unfortunately, even before the Great Library’s destruction, the city had lost some of its academic rigor. By the time of Hypatia, all that was left was the smaller sister library, the Serapeum, which served as a temple to the god Serapis.

The city also developed a reputation for violence. A multicultural hub, it wasn’t uncommon for various groups to engage in extremism and violence.

The Movie

Agora focuses on the life and death of Hypatia, widely considered to be science’s only martyr, for she was killed in a rather brutal way after at least one religious leader accused her of witchcraft for making astrolabes, which were tools used to study the stars before things like telescopes existed. In reality, she was likely killed more for political reasons, but we’ll dive into that later.

The film takes some substantial liberties with her life, but that’s also because there isn’t much to go on; this is both the good thing and bad thing about these types of movies. The subject matter is old enough and obscure enough that you can use a lot of artistic license without having to worry about academics breathing down your neck for inaccuracy, but you also know that you’re making up a lot of stuff due to a lack of sources.

The aim of the movie is to condemn extremism wherever it comes from. It uses a number of real-life events to establish the turbulence in the city that ultimately leads to Hypatia’s murder to condemn the same sort of religious extremism that exists in the world today. This movie came out in 2009, when Islamic terrorism was more in the public’s eye than it is today; but by using these historical events to shape its narrative, it manages to evade pointing fingers at anyone living today.

That doesn’t mean Agora escaped controversy. A number of people, usually Christians, condemned it for its portrayal of Christians, despite the fact that the portrayal actually is historically accurate. They tend to forget that the film is drawing on what occurred in Alexandria and isn’t reflective of the entire Catholic church at the time.

The fact that the filmmaker, Alejandro Amenabar, is an atheist, however, doesn’t escape me, especially as he made a point of saying before releasing the film. He does seem to have a slight agenda, but he typically doesn’t invent events and such to support his viewpoint. It doesn’t detract from the film or its accuracy, in my view.

I wish more people had seen this movie instead of it falling under the radar. This is a very interesting time period that encompasses the start of Christian persecution of Jews and pagans, the fall of the Roman Empire, and the end of the Classic period. There’s a lot of potential here for stories, but alas, most filmmakers won’t touch it.

What it Got Right

Before we get into the inaccuracies, it would be better to focus instead on what this movie gets right, and it gets a lot right.

The first thing I appreciated about this film was simply the way it depicted Hypatia herself. There’s a tendency in popular culture to view Hypatia as an ideal — a paragon of virtue and a thinker in a time of prejudice and willful ignorance.

While the film definitely shows Hypatia as being someone who values thinking and scorns the ignorance displayed by her peers (and this is supported by certain quotes of hers), it doesn’t portray her as being totally in step with our modern values. With her classist ways, most exemplified by the way she talks about slaves, the film shows that Hypatia was very much a product of her time.

In this way, the Christians are depicted as being ahead of the times. The film invents a fictional slave called Davis, who pines for Hypatia in secret, upset that he knows he’ll never have a chance with her due to his slave class. He’s in her classroom every day, yet she doesn’t consider him a student and barely regards him as more than furniture.

During one of her lessons, she asked her students why things fall to the ground when they drop them. However, she puts it by saying, “So, what mysterious wonder, do you all think, might be lurking beneath the earth that would make every single person and animal and object and slave settle there?” She doesn’t consider slaves to be worthy of being grouped with people, they exist in their own class, separate from the rest of the world.

She also says that the fighting in the streets is for “slaves and for riffraff.”

While the church is clearly portrayed as being sexist, especially at the film’s climax, the movie does do a good job of showing that, in regards to class, the church is doing better than the rest of the world in this regard. Davis ultimately converts to Christianity not because he’s naive or easily taken in, but because the church treats him like a human being. They show him that he’s both capable of being loved and showing love to other, more needy people. They also demonstrate that this isn’t a showing-off type of thing, that the church is big on charity and they take care of their own regardless of their past, their infirmities, or their social standing in secular life.

The movie also gets a lot of the events right. It condenses them and gets some details wrong, but it’s true that Christians threw stones at the Jews at the theater, that the Jews drew the Christians into a trap by pretending the church was on fire, and that the pagans sought to fortify themselves inside the Serapeum, which was destroyed by the Christians at the end of that conflict.

To start with the destruction of the Serapeum, it’s true that it was ransacked by Christians who were particularly anti-intellectual at the time. Ever since Emperor Constantine, the religion had been on the up and up, and now Theodosius I was on the throne. He could almost be considered a zealot and inadvertently emboldened a lot of local leaders to destroy pagan temples and artifacts.

The film neglects to point out that he attempted to completely outlaw pagan practices, instead narrowing the attack of the pagans on the Christians as being a reaction to the Christians desecrating and mocking their idols. Even without the wider political context, we can easily see how the pagans had underestimated the Christian population.

At this point in time, the pagan population knew that their influence was starting to wane, although they still held quite a bit of power. They also suspected that the Christian population was much smaller than it was — that it was just a small minority that was acting out as a way of paying retribution for centuries of torture and persecution. In reality, it was a lot of Christians who were eager to abolish the practices that both offended God and had allowed for their persecution.

The pagans holed themselves up within the walls of the Serapeum, just as we see in the film. They took Christian captives with them to act as hostages, shaken by the fact that their numbers were now so much larger than they anticipated.

Word of the situation was sent to Theodosius I. On the one hand, he felt it was his duty to abolish such places as the Serapeum. On the other, he also wanted to pardon the pagans who had taken refuge there. In the end, he declared the slain Christians martyrs and allowed the pagans to leave peacefully so long as they handed the Serapeum over to the Christians. The destruction that followed pretty much destroyed whatever hadn’t been destroyed in the Great Library centuries earlier.

Where most people assume this is a historical inaccuracy comes from mistakenly believing that Hypatia and the other pagans are within the Great Library itself. The dialogue that clarifies that this is actually the Serapeum, serving as the Great Library’s smaller, sister library goes by fairly quickly. We don’t know that Hypatia was involved in this at all, but we know that the event itself played out a lot like it did in the movie.

The Jews being evicted from the city after their attack on the Christians is also accurate. At that point in time, Cyril of Alexandria, or Saint Cyril, was the new bishop. This is quite a character! By this point in the film and in real life, he’d managed to gain enough influence that he rivaled the prefect, Orestes. While the movie against doesn’t go into the details or the full context surrounding it, it’s true that things were coming to a head between the Jews and the Christians, the pagans by this point be far, far fewer in number and holding almost no influence at all.

Cyril threatened severe retaliation against the Jews if the harassment of Christians didn’t immediately cease, and the Jews concocted a plot to draw the Christians out and attack them. They ran through the streets, shouting that the church was on fire. When the Christians rushed out to try and fight the fire, the Jews slaughtered everyone they could find. They used rings to recognize each other in the dark, ensuring they didn’t slay their own people.

Cyril responded by leading an angry mob of Christians and having all of the Jews rounded up, many killed, and banished from the city immediately, leaving their possessions to be ransacked by the remaining people. This put Cyril in an incredible position of power, and much of Orestes’ support came from the city’s former Jewish population.

What it Got Wrong

For all that it got right, there were some things that it definitely gets wrong. The first is, of course, the time skip. It’s true that there’s a time jump between the destruction of the Serapeum and Orestes’ feud with Cyril, but it was much bigger. Hypatia should be in her 50s or 60s by the end of the film, not just a few years older.

The film shows what I find to be a pretty good estimate of how Hypatia’s classes would have actually looked, but because this is a film about the price of being level-headed in a world falling apart due to extremism, they tend to focus in on her pursuit of knowledge. This would be fine, except that they give her the plot-line of exploring heliocentric thought, or the theory that the earth (and everything else in our solar system) revolves around the sun.

Now, for anyone thinking that this was an original of Galileo, it wasn’t. It was a theory that was already floating around by the time Hypatia was on the scene, but there’s no concrete evidence that she studied it herself. She may well have been perfectly at ease with the traditional Ptolemaic model.

This film also has an exchange that suggests that Hypatia may have been an atheist, but aside from a single made-up quote invented in 1908, there’s no reason to believe that she was. Hypatia was actually a Neoplatonist, which basically believes that there an ultimate being, above Zeus and other pagan gods, called the One. A byproduct of this being is the Intellect, which humans possess. Humans, according to this philosophy, have the ability, therefore, to reach the divine through meditation and sometimes ritual. This is likely what Hypatia believed, and Orestes likely allied himself with her specifically to endear himself to the pagans in the same way that he had previously done with the Jews.

On the note of Orestes, his role in history is as the prefect of Alexandria. While he was very close with Hypatia, there isn’t evidence that he was a student of hers, especially the specific student whose romantic advances she spurned by giving him her menstrual rags (a true event). This was likely done so that the character wouldn’t come out of nowhere after the time skip, and I don’t think it’s a bad change. It is an inaccuracy, though, and a large enough one for me to make a comment on it.

Obviously, the biggest change is Hypatia’s death itself. As Orestes’ and Cyril’s feud comes to its climax, Cyril attempts to discredit Orestes’ Christian credentials by asking him to disown Hypatia on the Biblical grounds that women shouldn’t hold the kind of power that he does. When he refuses to back down, Cyril manages to convince his followers that Hypatia practices witchcraft and should be killed.

There is some truth to this, but the movie doesn’t do it justice. Yes, Orestes got hit in the head with a rock, and, yes, Cyril took his retribution badly. However, he didn’t plan to dethrone Hypatia through Orestes or use the Bible to entrap Orestes.

He attempted to reconcile with Orestes, and showed him specific passages to lord over how he believed he had power over the secular role of prefect, which Orestes would have none of. Hypatia’s death had nothing to do with this wanton display of power.

Rather, Cyril was likely just jealous of Hypatia and the influence she held. She was, indeed, killed because she caught in the midst of their political rivalry, but it had nothing to do with Cyril’s confronting Orestes with the gospel.

In the film, Hypatia is beset by a mob and taken to a church. Before she can be killed, however, her former slave, Davis, suffocates her, sparing her the horror. This is possibly the worst offender in the film.

In life, it’s hard to tell for certain if Cyril was the one who set up Hypatia’s death. We know a lector named Peter was the one to actually lead the mob, but the historian Damascius points the blame directly at Cyril.

Hypatia didn’t walk into the streets to meet her fate; instead, she was waylaid on her way home and dragged to the church. She was stripped naked, like the movie, but there was no slave to save her. She was flayed alive, tortured unto death. Her limbs were hacked off and burned.

I find it odd that after a film like The Passion of the Christ came out, not shying away from the torture and death Jesus endured (unlike other Passion films) that this movie would downplay the one event of Hypatia’s life that is most recorded. If not for her violent and cruel death, we likely wouldn’t know much about her at all; she’d be a footnote in history, not the popular, enduring figure we know.

Have You Seen It?

Have you seen this movie? If so, what did you think? I really enjoyed this movie, and while this isn’t an exhaustive list of everything it got right and wrong, I hope I covered enough that you know what events were really changed and which are a good depiction of history.

As an aside, I created a shirt myself of one of Hypatia’s quotes. You can get it at Spreadshirt, Redbubble, or buy it here with BCH and other crypto!